The comedian Jerry Seinfeld once asked:

“What’s the deal with ‘homework?’ It’s not like you’re doing work on your home…”

The great thing about that quote is that it conveys that the “H” word has some of the most unpleasant associations for clients in CBT. In July 2016, Dr. Judith S. Beck and Dr. Francine Broder wrote an important contribution to the Beck Institute blog giving good reason for a move away from the “H” word in practice.

When developing Cognitive Therapy, Dr. Aaron T. Beck was inspired by existing therapies, including behavior therapy, wherein the educative model to generate clinically meaningful change had been adopted. The inclusion of homework as a crucial feature of Cognitive Therapy made perfect sense1. Homework is a collaborative endeavor. It is also ideally empirical and can help to promote the reappraisal of key cognitions2.

Asking clients to engage with therapeutic tasks between sessions, in a form of action plan has been subject to more empirical study than any other process in CBT3. However, the evidence supporting homework is almost wholly derived from dismantling studies that contrast CBT with CBT without homework, or correlational studies of homework adherence and symptom reduction. Findings from our most recent meta-analysis suggest that homework quantity and quality have little difference in their relations with outcome4. As clinicians, we can take from this that we should use homework consistently and be especially encouraged when clients engage with tasks5.

However, if we try to seriously answer Jerry’s question above, we have to ask ourselves another important question – what are we actually really interested in with CBT homework?

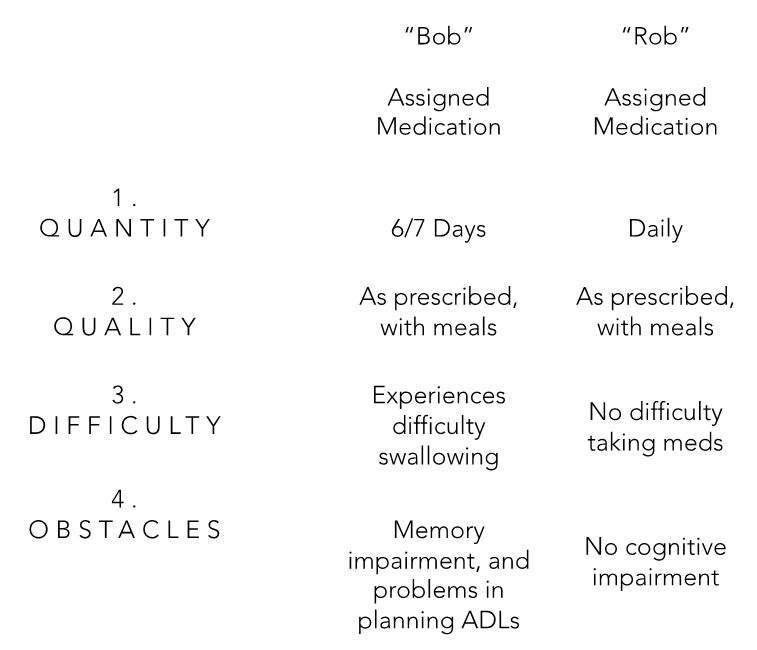

Current definitions of homework adherence have been derived from the literature on pharmacotherapy, and that might be the source of the problem. Take our two client examples below, Bob and Rob. Both have been prescribed a daily medication script, and if we look at the quantity of what was “done,” Rob looks more “adherent” than Bob.

However, when we take into account the cognitive impairment that Bob has, as well as his capacity to swallow medication following a head injury, then his 6/7 days’ worth of adherence is particularly noteworthy. Of course, in CBT, the content of homework varies on a weekly basis, and is tailored for the client in its design and plan. Therefore, the scope for subjective views of difficulty, and array of unique practical barriers is considerable. Thus, if we are genuinely interested in “engagement,” we need to take into account the inherent difficulties of the homework and practical obstacles to it for each individual client, at each session6.

Dr. Judith Beck’s earliest teachings emphasize the importance of the client’s subjective evaluation of homework. Those who are depressed are less likely to recognize their achievements, those with anxiety presentations often have negative predictions about its utility or their ability to carry it out, and many clients abandon the task when encountering obstacles. Those with pervasive interpersonal difficulties often have their core beliefs triggered in carrying out the action plan. When they do, they may experience intense negative emotion, viewing themselves and/or their therapist negatively. The working alliance may become strained. Dr. Beck has also advocated for use of the cognitive case conceptualization to understand clients’ patterns of engagement and anticipate problems of this nature7-8.

Fortunately, the research underpinning CBT homework is moving towards more clinically meaningful studies. Therapist skill in using homework has been shown to predict outcomes9-10, and recently a study found that greater consistency of homework with the therapy session resulted in more adherence.11 Our Cognitive Behavior Therapy Research Lab (currently based at the Turner Institute for Brain and Mental Health at Monash University) is centrally focused on how clients’ adaptive beliefs about homework strengthen their sense of self-efficacy in engaging in homework tasks, despite the difficulties and obstacles they experience. Thus, for several reasons, we can be optimistic that the evidence for homework is an example of how a bridge between science and practice is being built on solid foundations.

A half century after the first practice guide for Cognitive Therapy was published (Beck et al, 1979), we can be curious in the personal meaning our clients attribute to the action plan. How do beliefs about coping and change affect engagement? Are there important maladaptive assumptions and compensatory strategies that might make it difficult for the client to engage? How does the task align with the client’s values? What might be the pros and cons to the client in choosing not to engage? It’s important to focus less on trying to achieve perfect – or even a close approximation of perfect – “adherence” and to focus more on facilitating engagement. An empathic understanding of challenges clients face completing the homework tasks will better equip us to design and plan future homework. Rather than a focus on “compliance,” let us inspire our clients to tolerate the discomfort and uncertainty in their homework. Let us also celebrate in their discovery of new ideas and perspectives that homework brings.

Nikolaos Kazantzis, PhD is Editor of “Using Homework Assignments in Cognitive Behavior Therapy” (2nd edition), currently in preparation with Routledge publishers of New York.

References

- Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press.

- Kazantzis, N., Dattilio, F. M., & Dobson, K. A. (2017). The therapeutic relationship in cognitive behavioral therapy: A clinician’s guide. New York: Guilford.

- Kazantzis, N., Luong, H. K., Usatoff, A. S., Impala, T., Yew, R. Y., & Hofmann, S. G. (2018). The processes of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 42(4), 349-357. doi: 10.1007/s10608-018-9920-y

- Kazantzis, N., Whittington, C. J., Zelencich, L., Norton, P. J., Kyrios, M., & Hofmann, S. G. (2016). Quantity and quality of homework compliance: A meta-analysis of relations with outcome in cognitive behavior therapy. Behavior Therapy, 47, 755-772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2016.05.002

- Callan, J. A., Kazantzis, N., Park, S. Y., Moore, C., Thase, M. E., Emeremni, C. A., Minhajuddin, A., Kornblith, S., & Siegle, G. J. (2019). Effects of cognitive behavior therapy homework adherence on outcomes: Propensity score analysis. Behavior Therapy, 50(2), 285-299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2018.05.010

- Holdsworth, E., Bowen, E., Brown, S., & Howat, D. (2014). Client engagement in psychotherapeutic treatment and associations with client characteristics, therapist characteristics, and treatment factors. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(5), 428–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.06.004

- Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive therapy for challenging problems: What to do when the basics don’t work. New York: Guilford.

- Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford.

- Weck, F., Richtberg, S., Esch, S., Hofling, V., & Stangier, U. (2013). The relationship between therapist competence and homework compliance in maintenance cognitive therapy for recurrent depression: Secondary analysis of a randomized trial. Behavior Therapy, 44(1), 162–172. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2012.09.004

- Conklin, L. R., Strunk, D. R., & Cooper, A. A. (2018). Therapist behaviors as predictors of immediate homework engagement in cognitive therapy for depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 42(1), 16–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-017-9873-6

- Jensen, A., Fee, C., Miles, A. L., Beckner, V. L., Owen, D., & Persons, J. B. (in press). Congruence of patient takeaways and homework assignment content predicts homework compliance in psychotherapy. Behavior Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2019.07.005