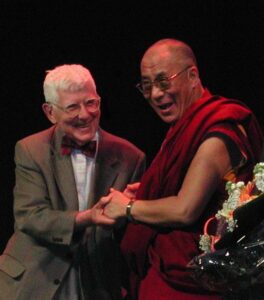

Aaron T. Beck, M.D.

Göteborg June 13, 2005

Judy Beck and I met with the Dalai Lama initially in his private drawing room in the hotel for an informal discussion a couple of hours prior to the actual public dialog. Also attending were Paul Salkovskis, Astrid Beskow, and a number of his own representatives, including his long-time interpreter. Initially, I presented His Holiness with a copy of Life magazine from 1959, which had a cover picture of him receiving bouquets from his American supporters after his escape from Tibet to the United States. He seemed pleased to see this much younger picture of himself. I also presented him with a hard copy of Prisoners of Hate. He seemed taken by the title, which epitomized his own view that hatred imprisons the people who experience it. He then remarked that there must be six billion prisoners in the world!

On a personal level, I found him charismatic, warm, engaging, and very attentive to what I had to say. At the same time, he seemed to maintain an objective detachment not only with me but also with the members of the entourage. He also impressed me with his wit and wisdom and his ability to capture the nuances of very complex issues.

The dialog was held at the Göteborg Convention Center with about 1400 attendees at the International Congress of Cognitive Psychotherapy. In keeping with his expressed wish, I started the dialog. I began to recite the dozen or so main points of similarity between Tibetan Buddhism and cognitive therapy (listed below). After I recited four or five similarities, he interrupted with the statement that they were as many items as he could absorb at one time.

My main challenge in the dialog was to inform him about the cognitive approach to human problems without in any way taking away from the broad philosophy and psychology of Buddhism. My strategy was to find appropriate points in his discourse where I could introduce cognitive concepts that were relevant in some way to his train of thought. I tried to represent the cognitive approach as a valid system or discipline in its own right that overlapped but also was complimentary to Buddhism. I also had to be conscious of my choice of words. Although His Holiness is quite fluent in speaking English, he is not familiar with more technical words, especially those for which there are no Tibetan equivalents. For example, he used the term “negative thoughts,” which I repeated in preference to the more technical (and precise) cognitive terms, such as self-defeating thoughts or dysfunctional cognitions.

Among the points that I brought up, which he then expanded on from his own vantage point, were that both systems use the mind to understand and cure the mind. Acceptance and compassion were key similarities. Also, in both systems, we try to help people with their overattachment to material things and symbols (of success, etc., something we call “addiction”). I gave a case example of a depressed scientist who was so attached to success (in this case, specifically winning a Nobel Prize) that he excluded everything else in his life, including his family. I had used a typical cognitive strategy to give the patient perspective. In the course of a single session, he changed his beliefs and got over his depression (at least temporarily). The Dalai Lama’s response to this anecdote was, “You should get the Nobel Prize for Peace.”

Another point that I brought up was our distinction between pain and suffering. I suggested that much of people’s suffering is based on the fact that they identify themselves with the pain. People who are able to separate (“distance”) themselves from the pain and view it more objectively had significantly less distress (as pointed out by Tom Sensky’s group in London). His Holiness seemed taken with this concept and then said in an amusing way that maybe he could use this notion to help himself with his chronic itch. (This half-serious comment, of course, evoked a large amount of laughter from the audience.) He later referred to cognitive therapy as similar to “analytical meditation.”

I asked His Holiness how he thought that his message could really take root in the world. He then expanded on his ideas that education had to be the answer. He also expressed his own philosophy, which he described as secular ethics. Although people of different faiths could embrace the values that he expressed, such as total acceptance of all living things, he did not feel that religion was a necessary instrument for this. He appeared to echo what is also the essence of the cognitive approach, namely self-responsibility rather than depending on some external force to inspire ethical standards. Since I believe that CT also regards unethical and morally destructive behavior as a cognitive problem and thus would advocate a “cognitive morality,” I later was able to get this point across but in different words. When he asked me for my view of human nature, I responded that I agreed that people were intrinsically good but that the core of goodness was so overlaid with layer after layer of “negative thoughts” that one had to remove the layers for the goodness to emerge. He expressed the belief that positive thinking (focusing on positive and good things) was the way to neutralize the negative in human nature. My position was that the best way to reach this goal was to pinpoint the thinking errors and correct them. After we concluded the dialog, Paul Salkovskis gave an outstanding summation of the topics that we had covered.

Since Astrid Beskow (the prodigious organizer of the event) discovered that by coincidence this was his birthday, there was a short birthday celebration during which he was then given a large bouquet. He then gave Astrid, Paul, and myself a Buddhist prayer shawl. I later learned from an intermediary that he enjoyed the dialog and that he would think about several points that I raised.

All in all, it was a thrilling experience for me and, from what I heard from several of the attendees, also for the audience.

From my readings and discussions with His Holiness and other Buddhists, I am struck with the notion that Buddhism is the philosophy and psychology closest to cognitive therapy and vice versa. Below is a list of similarities that I suggested to the Dalai Lama in our private meeting. Of course, there are many strategies we use such as testing beliefs in experiments and formulating the case that are not part of the Buddhist approach.

SIMILARITIES BETWEEN COGNITIVE THERAPY AND BUDDHISM

- Goals: Serenity, Peace of Mind, Relief of Suffering

- Values:

- Importance of Acceptance, Compassion, Knowledge, Understanding

- Altruism vs. Egoism

- Universalism vs. Groupism: “We are one with all humankind.”

- Science vs. Superstition

- Self-responsibility

- Causes of Distress:

- Egocentric biases leading to excessive or inappropriate anger, envy, cravings, etc. (the “toxins”) and false beliefs (“delusions”).

- Underlying self-defeating beliefs that reinforce biases.

- Attaching negative meanings to events.

- Methods:

- Focus on the Immediate (here and now)

- Targeting the biased thinking through:

- Introspection

- Reflectiveness

- Perspective-taking

- Identification of “toxic” beliefs

- Distancing

- Constructive experiences

- Nurturing “positive beliefs”

- Use of Imagery

- Separating distress from pain

- Mindfulness training